-

The Elusive Element of Regional Urban Resilience and Social Awareness in Cities

-

- 29 April 2017

- Kililo Mtamu Peninah Mutonga

- Opinion , Editor's Choice , Articles Books & Magazines , City Planning , Public Spaces , Great City Terrible Place ,

In this article, Originally presented for the 2016 Architectural Association of Kenya Annual Convention Publication in 2016, the idea of regional Urban Resilience is explored by archiDATUM's editor's Kililo Mtamu and Peninah Mutonga.

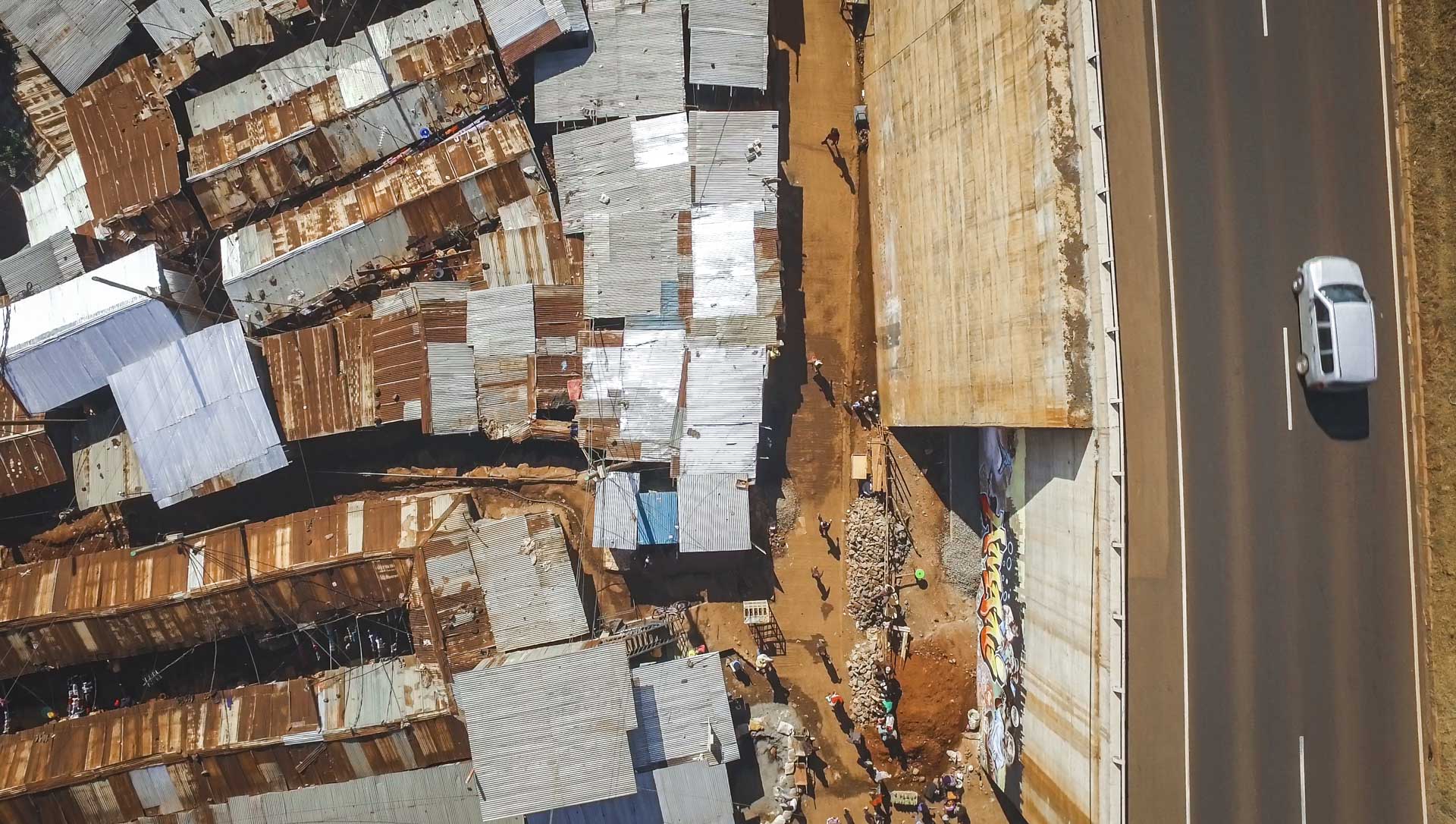

With urban sites being places where the large percentage of the population dwells to alter their economic situation, large cities have become home to high concentrations of poverty. The motivations and forms of concealing this reality have resulted in large inequalities manifest in conflict and other forms of social disability palpable in the region today. In greater expansion, conflict can and should be ultimately viewed as a progressive aspect for societal development. As different cultural groups interact, and integrate, opposing ideas, mandates and ideologies complect and entwine. Therefore, these are regenerative ideas society must face- a phase we can only hope is intermittent

The real challenge facing our cities is that of eradicating poverty and poverty-related living conditions. Urban resilience, then, must be geared towards the core role of the city concept. If our cities are not alleviating poverty, then they are failing, and if they are alleviating poverty and failing to change our physical environment, then the entire profession [and practitioners] of the built environment is failing with it. The culture of informality, which is not a new framework of city concepts, is the emerging sign of popular economy for this region. While urban sites have become a breeding ground for informal practices as a means of survival for the vast majority of city dwellers, urban theory and practice has not adapted to new ideologies and rising urban challenges. For a while now, we have been applying old remedies to city disease mutations- the consistent failure of which, has rendered urban stakeholders paralysed. Birthed in the city, the resultant situation of informality has penetrated and consumed the region in many guises; from the ‘informal’ practices in government offices to informal markets, and right down to its physical manifestation in settlement and housing patterns. Informality has become a culture we have accepted and even began to ‘formalise’. One of the best examples of the ‘formalised’ informal market is the MPesa, discussed rigorously in Dayo Olopade’s The Bright Continent: Breaking Rules and Making Change in Modern Africa.

Transport Struggles In Lagos_Nigeria's Population is Now World's 7th Highest

The paradigms in the region are shifting and its high time professionals [and practitioners] improvise rather than compromise ‘western school’ training to fit the rapidly changing African urban context. The average person wants what is convenient and affordable; if we are not providing decent solutions to these needs, then the profession can be declared redundant and rather a source of livelihood for a privileged few. The development of fundamentally new concepts for creating sufficient living spaces for a growing population stands a better chance at being commensurable with this growth other than the said conservative means. The concepts must be socially robust, open and flexible in their spatial structure and usage. The introduction of innovative building techniques and the lowest maintenance requirement possible is a central point that architects, planners and urban designers need to focus on. Alternative building technologies continue to push the boundaries and introduce efficient and effective ways of constructing at reduced cost. Materials like earth, thatch and plastic have been deployed to wonderful effect and can significantly cut the cost for constructing a unit.

Aerial Images of Rem Koolhas and Kunle Adeyemi of a Bustling Congestion in Lagos Public Areas

For most Sub-Saharan countries, the brick and mortar has become synonymous with housing structures that are considered durable, functional and associated with success. However, their level of success is wanting and the case of the ghost town in Kilamba, Angola some 30km from Luanda or the Slum Upgrading Project in Kibera, Nairobi are some of the projects that prove that the brick and mortar high-rise building will not meet the high housing demands or the social demands of the highly growing urban population. Most of these structures have remained unoccupied or ended up as slum ‘relocation’ rather than upgrading projects. Architecture is after-all a social science, a careful navigation of societal oddities and cultural norms into spatial dispositions that then form communities. It is more than architecture in its strictest profession and most of these social projects have declared that vehemently.

Admittedly, the nature of the political context and economy is perhaps the most critical ‘nuisance’ for the urban case but a commitment and idealism to social responsibility must remain at the forefront if we are to discuss urban resilience in the twenty-first century. Nearly all the major urban centres in Sub-Saharan Africa are facing a housing deficit that is growing exponentially and requires urgent, efficient, appropriate and sustainable solutions to even start cutting it down. Heavy urbanization is choking the already existing planning methods in building techniques and housing policies. Land and building material costs have become beyond reach for the would be first home owners in the growing urban environment. As a developing region, we can borrow a leaf from the incremental housing works of the 2016 Pritzker Award winner Alejandro Aravena. His approach, which is likely to work in urban centres, revolves around participatory planning methods with integrated strategies and systematic changes. With proper input from the governing authorities, the urban population is basically left with a dynamic shell that they grow around and with. This participatory approach is more welcome and appreciated by the society and allows urban dwellers to build according to their needs. In any case, this concept is not all new to our traditional settlement patterns.

Alejandro Aravena, 2016 Pritzker Prize Winner, Shows Us How Low-Cost Architecture Is Done

The Swahili for example, developed a pattern where they build and expanded their houses vertically and horizontally around a courtyard as the family and clan expanded. The plan, which offers the basic elements of a house at a low budget, and encourages residents to expand into an adjacent space as they find money to do so, will be available for architects worldwide to learn from. The collaboration works between EiABC (Ethiopian Institute of Architecture Building Construction and City Development), Bauhaus-Universität Weimar and ETH Zürich have seen a number of similar building proposals in Ethiopia. These solutions, the MACU, SICU and SECU may have their shortcomings but are geared towards alternate solutions that in the future may solve the housing deficit challenge for large cities.

Builiding For The Gap_EiABC, Bauhaus Universität Weimar_MACU

In addition, it is worth considering the cultural perceptions of city living for this region which has focused on the city as a temporary place for those who ‘plan to go home eventually’. Whilst most city ‘dwellers’ aim at ‘living’ -meaning surviving- in the city until they are able to build a home in the village, legal acquisition of land has become unaffordable if not impossible for some. These are ideologies we should build upon. Based on our resource allocation and lack of state finances to deal with the rapid urbanization, ambitious governments may opt to shift their focus to small cities and towns where rapid urbanization is possibly on a higher rise than that in the larger cities. Professionals and investors should follow suit. The UNFPA in 2008 concluded that ‘while mega cities have captured much public attention, most of the new [population] growth will occur in smaller towns and cities.’ An excerpt from UN in 2012 provides a clearer picture of the urbanisation dynamics in the region, ‘Africa has a distribution of the urban population by size of urban settlement resembling that of Europe, with 57% of urban dwellers living in smaller cities (those with fewer than half a million inhabitants) and barely 9% living in cities with over five million inhabitants.’

This blatantly sounds a siren for the need for collective public investment in smaller cities. The term investment here does not necessarily refer to mega-built projects of the ‘political’ dimension we have witnessed in recent times. While that is commendable and may give rise to economic development, it is equally promoting greater inequalities within large cities. The challenge with mega-(infrastructure) projects is that they are focussed on connecting bigger cities rather than growing smaller towns. Public investment, here, calls for a paradigm shift from focussing on big cities to smaller cities and towns. This means desensitizing [since we are constantly failing at decentralizing the populous - professionals involved. Living in large concentrations -urbanization- having been conceived by capitalism, is a concept foreign to the African context. Urban resilience for the region will arise when leaders in economic circles, the built environment, and institutions of architecture and urban planning re-align their perceptions of what urbanization for the region ought to be.

Focus Should be on localizing and formalizing informal markets like the rapidly growing Lagos atmosphere

A focus on ‘localization’, formalizing informal markets, creating industries, promoting manufacture and distribution of locally produced commodities, providing decent housing and civic infrastructure and managing climate change in rural and peri-urban settlements, are ideas that should take center stage in urban and investment forums. The potential for small cities and towns is immense and professionals should engage in ideas that multiply ‘semi-cities’ rather than enlarge already existing ones. While this approach may not tackle the current problem of urban housing deficit, it is a long-term goal requiring major changes in policies, professional training, and central government expenditure.

Urban resilience for this region is not simply a building and planning procedure; it is a complex interdisciplinary integrative plan. With the urban population estimated to grow by 70% by 2025, it is urgent for professionals in this region to re-invent urban practice by interweaving indigenous living ideologies, construction technologies, and socio-economic activities, with modern planning methods and policies.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

-

If you want your own avatar and keep track of your discussions with the community, sign up to archiDATUM >>